Aria Mineralia

Larisa Crunțeanu, Aria Mineralia Zachęta Project Room, Warsaw, October 20 – December 2, 2018.

Larisa Crunțeanu, Installation view of “Untitled,” HD split-screen video, 10’, 2018, and “Untitled,” two ceramic objects realized in collaboration with Olga Milczyńska and August Studio, 2018. Image courtesy of the artist.

For her exhibition Aria Mineralia at Zachęta Project Room, Larisa Crunțeanu, a Romanian-born, Warsaw-based artist and curator, has created a sound-based installation along with accompanying ceramics, neon, costumes, and video works that all address notions of camouflaging as an activity of playful subversion.(Aria Mineralia at Zachęta Project Room, Warsaw, is part of the cultural project F vs F, produced by Copia Originala Association and co-funded by the National Cultural Administration Fund, Romania. Partner of the exhibition: Anca Poterasu Gallery.) The title Aria Mineralia refers to the music term “aria,” a melody composed for one voice without accompanying instruments, while “mineralia” refers to minerals or the nonhuman. As such, the show’s title invokes its main subject: a plastic, rock-shaped speaker that in fact broadcasts Crunțeanu’s singular digitally altered voice, although it is duplicated to sound multiple. The rock itself is presented as a functional speaker but also replicated in two ceramic sculptures that are rendered impotent through the material change and literally become semblances of the original form. This speaker itself is modeled off of a readymade object that Crunțeanu and artist Sonja Hornung found outside of the Palace of the Parliament in Bucharest – a large autocratic building second in size only to the Pentagon in the United States. The speaker, as the artists later found out, was meant to sound folk songs and was connected to the mayor’s office of the city; however, due to some failure in the cybernetic circuit, the plastic rock stayed silent, refusing in a way the stereotypical Romanian folk music it was programmed to play. The exhibition as a whole can be seen as a response to the many paradoxes within the contemporary neoliberal, post-socialist city of Bucharest, where performativity, mimicry, and plasticity have become a means to clout inconvenient political pasts and presents.

Laris Crunțeanu, Installation view of “Esprit de Corps,” 12-channel sound installation realized in collaboration with Laurențiu Coțac, 2018. Image courtesy of the artist.

Crunțeanu’s practice spans installation, performance, and film, and often includes collaborations with friends such as the aforementioned Hornung. Collaboratively Hornung and Crunțeanu produced a body of work Femina Subtetrix,(https://www.artmargins.com/index.php/exhibitions-sp-132736512/777-femina-subtetrix-a-feminist-look-at-the-apaca-textile-factory) an exhibition in Bucharest’s Ivan Gallery that examined the notion of female textile labor in pre- and post-socialist Bucharest. In 2017, Crunțeanu held an exhibition at the Romanian Cultural Institute in Berlin titled Seeds (planted by other women inside my head) that specifically addressed her collaborative practice with other women artists. Notably, one can see that all the works in Aria Mineralia have been created collaboratively.

For the past several years, Crunțeanu has been based in Warsaw. Aria Mineralia, which was previously exhibited at Anca Poterasu Gallery in Bucharest, delves back into many themes the artist had previously been working with: the notion of the female laborer in post-socialist, privatized Romania, as well as staging roles that are often projected onto the self in the now neoliberal, capitalist city. As such, the contexts of Warsaw and Bucharest become important lenses to view Aria Mineralia. The paradoxically left-wing government in Romania recently was critiqued for its fiscal corruption, while the right-wing populist government of Poland presents other challenges for artists who don’t cohere to the nationalist paradigm. On the level of aesthetics, it is not uncommon to see a socialist building in Warsaw covered with a cheap plastic banner of the Chinese telecommunications multinational Huawei, which seems initially humorous yet telling of the process of privatizing space that once had communal aspiration, even if real existing socialism complicates the latter.

Larisa Crunțeanu, Detail of “Esprit de Corps,” 12-channel sound installation realized in collaboration with Laurențiu Coțac, 2018. Image courtesy of the artist.

Spatially, the exhibition begins with the installation Esprit de Corps that consists of twelve decoy rocks – kitchy prefab commodities that also function as audio speakers. These rocks have been arranged on the ground to form a circle, while a green neon light sculpture, hung directly above, mimics this circular shape. Between the green light and the beguiling sounds, the scene immediately feels like a séance that is taking place without the people or ritual ceremonies. The sound coming from this thirty-minute, twelve-channel sound installation (produced in collaboration with Laurențiu Coțac), is comprised of a chorus of voices and digitally composed sounds, for example an army marching. Another sound is an army salute that in real life plays once a day in Krakow to mark a famous battle where the city was protected against the Mongols. Here in the space, the sound is disconnected with reality and becomes just a simulation of the now ritualistic trumpet sounding. The late French war scholar and postmodernist Paul Virillio remarked how it was the simulation of war on CNN and television screens that took the place of the actual battle front in the Gulf War.(Paul Virilio, Desert Screen: War at the Speed of Light, translated Michael Degener (London: Continuum, 2002).) The activities of war changed in order to become media spectacles, and today we can see how the media spectacle is still changing war when examining the way the Islamic State has used media to terrorize. Though these specific references are absent within Esprit de Corps, they nonetheless hang in the air.

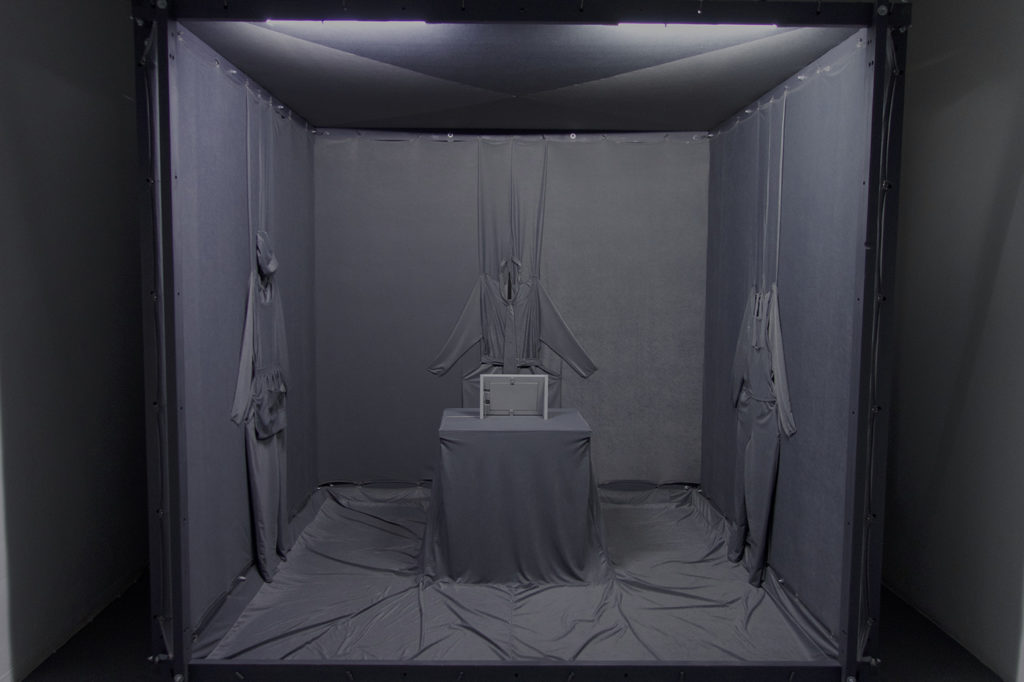

Larisa Crunțeanu, Installation view of “A Conversation Between Three Workers . . .” realized in collaboration with Magda Vieru, Octavian Hrebenciuc, Atelier Tron, Atelier Vast, 2018. Image courtesy of the artist.

Crunțeanu explains in a conversation with the writer that this specific trumpet call and its ritual sounding in Krakow is one that she has grown fond of since living in Poland because of its mythology and evolution to a more nationalistic sound. In fact, the military and its memorabilia within the context of Poland is often connected with nationalistic sentiments as it is in most post-Soviet countries. In one of my first visits to Warsaw, I witnessed the streets being paraded with military tanks and weaponry, which happens every mid-August to mark a battle of the Polish Army’s resistance to the Red Army in 1920. Though perhaps a normalized occurrence in Poland, this show of military might and its allusion to violence was shocking in comparison to national days in, for example, the United States and Canada, countries that I grew up in and that perhaps flex their violence through other rituals and means. The ritual sounds of this annual festival parade are similar to the simulated sounding of a trumpet in the Zachęta Project Room. Although the actual violence of the event is missing, its simulation recalls something much more threatening when considered within the context of broader military histories. The work’s title, Esprit de Corps, is a military term that means a feeling of pride generated through fraternity, but whose literal translation means spirit or ghost of a body. This feeling of fraternity is similarly devious and something that the Pakistani military historian, Ayesha Siddiqa, writes is a tool that is tied to the private profit of military personnel in the commercial sector.(See Ayesha Siddiqa, Military Inc. (London: Pluto Press, 2007). Former retired soldiers get jobs based upon this fraternity in the private sector and cross between the public state body and the individual one. Both the military definition of esprit de corps and its literal meaning translated from the French touch on a more abstract sense of camouflaging that happens when a singular person enters a pack, a chorus, or a multitude, and loses singularity.)

Larisa Crunțeanu, detail of “A Conversation Between Three Workers . . .” realized in collaboration with Magda Vieru, Octavian Hrebenciuc, Atelier Tron, Atelier Vast, 2018. Image courtesy of the artist.

Adjacent to Esprit de Corps is an untitled installation, comprised of two handmade ceramic sculptures modeled after the rock speaker, and presented in front of two flat-screen TVs that represent the original scene in Bucharest. The mirroring and levels of removal from the original weave an interesting web of simulations and simulacrums, as there is no real or original object or representation of the real speaker in the space, but rather only likenesses. This multiplicity of likenesses becomes Crunțeanu’s own definition of what camouflaging is: something that mimics but also resists through dysfunction. This theme is most directly apparent in the video No Image, No Camouflage 2018), where Crunțeanu’s body is keyed out of the frame thus only the absence of a body remains in the scene.

Larisa Crunțeanu, “A Small and Insignificant Love,” video still, 2018. Image courtesy of the artist.

Although versed in installation, Crunțeanu often works in performance and acts in many of her own film projects. Her feature film A Small, Insignificant Love (2018) is an adaptation from the Romanian reality-telenovela Forbidden Love that the artist starred in years ago in Bucharest. The artist received a one-episode role after trying out for a series of open calls as an artistic research project that she began in the early 2000s with Xandra Popescu. The aim wasn’t to find the right role or job but to play at acting and to question roles already evident in the play of self. For example, Crunțeanu’s film imagines the ending of all of the characters from the episode she appeared in, whom she also interviews in a type of meta-analysis of the scene.

For Crunțeanu, this shifting and transitioning away and to the self becomes another form of hiding in plain sight that also riffs on the backdrop of post-socialist Romania’s de-communization process and current free labor market. For instance, at the end of the film, one of the main female characters reveals that she has a husband who is working in America; she must return to him, which shatters a love triangle and ends her affair with a younger man. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, many people living in former communist countries went to the West in search of jobs, as the currency was much stronger and valuable comparatively. This plunged many workers into a state of precarity by working on construction sites in the West without fixed contracts, sometimes having to return back without pay. The Yugoslavian-born, Berlin-based performance artist Tanja Ostojić similarly touched upon this inequality and the precarity associated with crossing the border for Eastern European women in her project I’m looking for a Husband with an EU Passport (2000-2005). The artist used her own body as an object of exchange to enter into the European Union labor and artistic market. While Crunțeanu’s humor is not as satirical as Ostojić’s, there is a similar crossing of reality and art, making visible the precarity placed on women’s bodies whose only means of resistance become over-performance of the stock roles they have been given. Ostojić married an artist from Cologne and divorced him some years later, both acts performances. In A Small, Insignificant Love, Crunțeanu is also interested in the ways characters come together and play themselves in soap operas, but this naturally carries to the everyday as well. Crunțeanu’s own character is a rich, spoiled daughter who tries to buy back her boyfriend’s love after he cheats on her with a much older woman. The scene is all about malfunctioning and story lines happening that do not fit to the stereotypical view of heterosexual love. The younger woman, Crunțeanu, gets left for the older woman and plots a way to right her storyline, which makes the plot even more dysfunctional.

Crunțeanu has extensively researched labor contextualized within the Central and Eastern Europe, as in her collaborative project with Sonja Hornung, Femina Subtrix, which focused specifically on the APACA factory that employed female textile workers and today lies derelict after being closed for some decades. The last installation for Aria Mineralia, A Conversation Between Three Workers…, once again takes on the notion of the female laborer, explored through costuming and uniforms that are all made out of an austere color of grey. Crunțeanu’s installation resembles a barren theater set. The work is one massive piece of gray cloth tacked to scaffolding and three uniforms fashioned into different kinds of work garments – that of a cleaning lady, an office worker, and a construction worker. In the middle of these fabric costumes is a tablet computer that depicts Crunțeanu humorously trying on all of the uniforms as if to judge the size. Crunțeanu, who is the sole performer, stares into the camera while striking different power poses. In one, her back is bent and her arms are crisscrossed over the table. The austerity of the image recalls a Kafkaesque aesthetic and specifically resembles his famous short story Metamorphoses where the protagonist becomes an animal. Like Gregor who has to undergo a “becoming” in order to destabilize the tight, triangular family structure of early twentieth-century Prague, Crunțeanu too becomes an office worker, a construction worker, and a cleaning lady. These various transformations highlight the deterritorialized reality of life in the current neoliberal labor market where workers have to perform multiple tasks and skills in order to stay fungible. In a conversation with the writer, Crunțeanu explains how these costumes and the reason for choosing these professions came out of her own experiences growing up in Romania where the singular term “worker” changed during the political transitions and suddenly was no longer in use. Her parents, who worked in a factory before 1989 were just identified as “workers,” but as time progressed their labor needed to be specified. She jokes that she only knew her parents’ jobs as factory workers, but in neoliberal aspiring, post-socialist Romania, they would probably be called heavy duty operators.

Aria Mineralia is full of mimics, jokes, echoes, and translations that, at times, could seem surprising given that this theoretical language was born out of 1980’s poststructuralism and earlier minimalism. However, when read closely against today’s political climate and the rise of right-wing populism, semantics and simulation become natural byproducts of the times, especially because these oppressive forces often include budget cuts to the arts or as in the case of Romania, corruption. Also at play within Aria Mineralia is how the self is portrayed or multiplied in neoliberal labor markets and how the change from the singular uniform image of the worker has produced a type of shock to the children of communism, who unlike those of us in the West, haven’t been indoctrinated with the high-performance rhetoric of efficiency.